My career in education, although brief, has been quite diverse and allowed me to experience the educational process from multiple perspectives. I worked as a high school teacher and a lecturer in England, and during each of these phases, I grew more and more fond of creative pedagogies and their impact on education. Most recently I have been working as a Pedagogy and Assessment officer at AUC’s Center for Learning and Teaching, and have started doing a lot more research in relation to course design.

I recently became enamored with the concept of gamification after attending a conference workshop on the topic. I was hooked and began my journey of discovery of books, blogs and workshops on gamification. As with any new concept in any field, there is only a limited amount of research on the subject and slightly the different definitions of each for the concept of gamification is slightly different. The definition I prefer is the one provided by Karl Kapp (2012): “Gamification is using game-based mechanics, aesthetics and game thinking to engage people, motivate action, promote learning, and solve problems.” Definitions of game mechanics, aesthetics and thinking are all defined in a earlier edition of New Chalk Talk titled Game On! (Morcos, 2014)

I decided to take my first venture into gamifying my syllabus, partly due to my curiosity as a faculty developer, to see how this plays out in practice. But I was also intrigued with the notion of tapping into students’ intrinsic motivation. I decided to follow the advice I regularly give to faculty during consultations and start small and by only gamifying a part of my syllabus to see how that would go. I was initially apprehensive, as I was teaching full time in-service teachers and was concerned that gamification might be too childish for them. I quickly overcame any concerns the minute I began researching the topic, due to the fact that most gamification that has taken place has been for enterprises and businesses to engage their clients and personnel.

This article is my reflection on the experience as a whole with the lessons learnt and future directions.

I teach a course titled ‘Productivity and Professional Practice’ as part of the Professional Educator’s Diploma, a Teacher development program at the Graduate School of Education. The course focuses on the importance of professional development for in-service teachers and how they can take charge of their own development by utilizing technology.

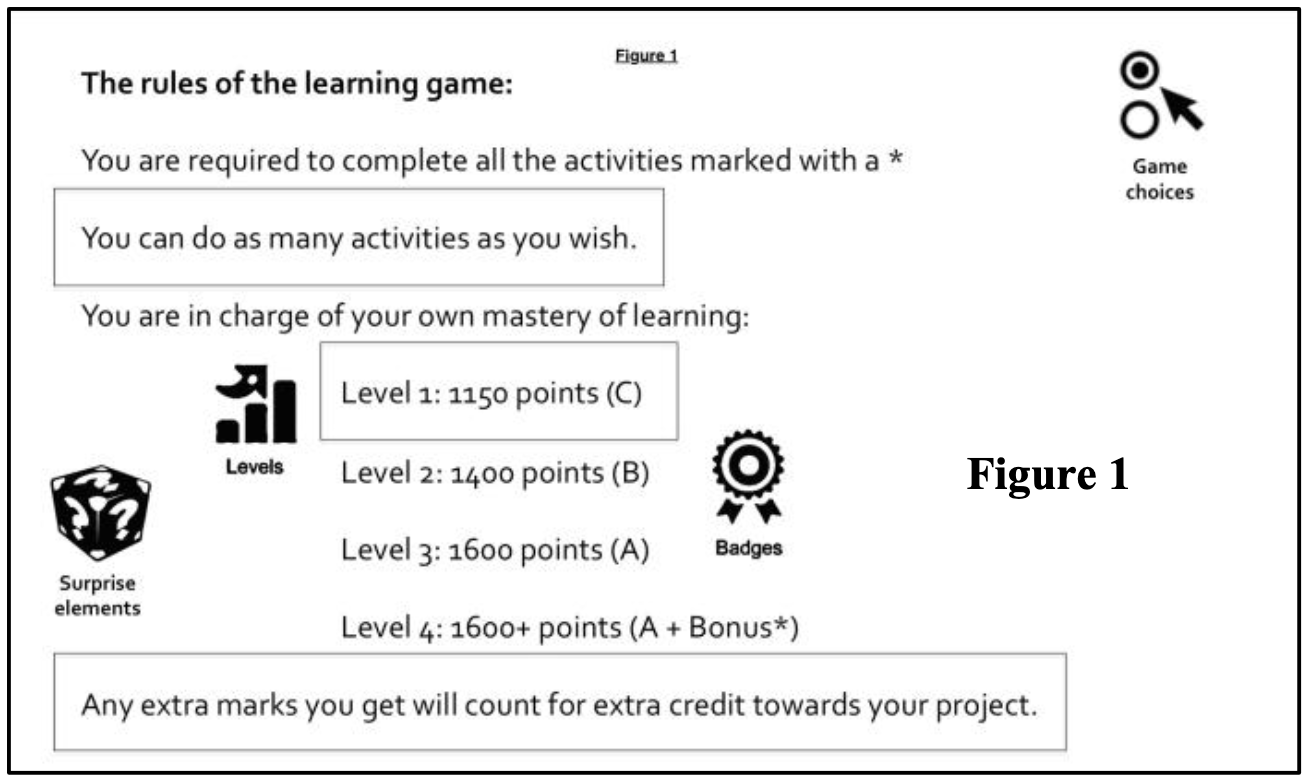

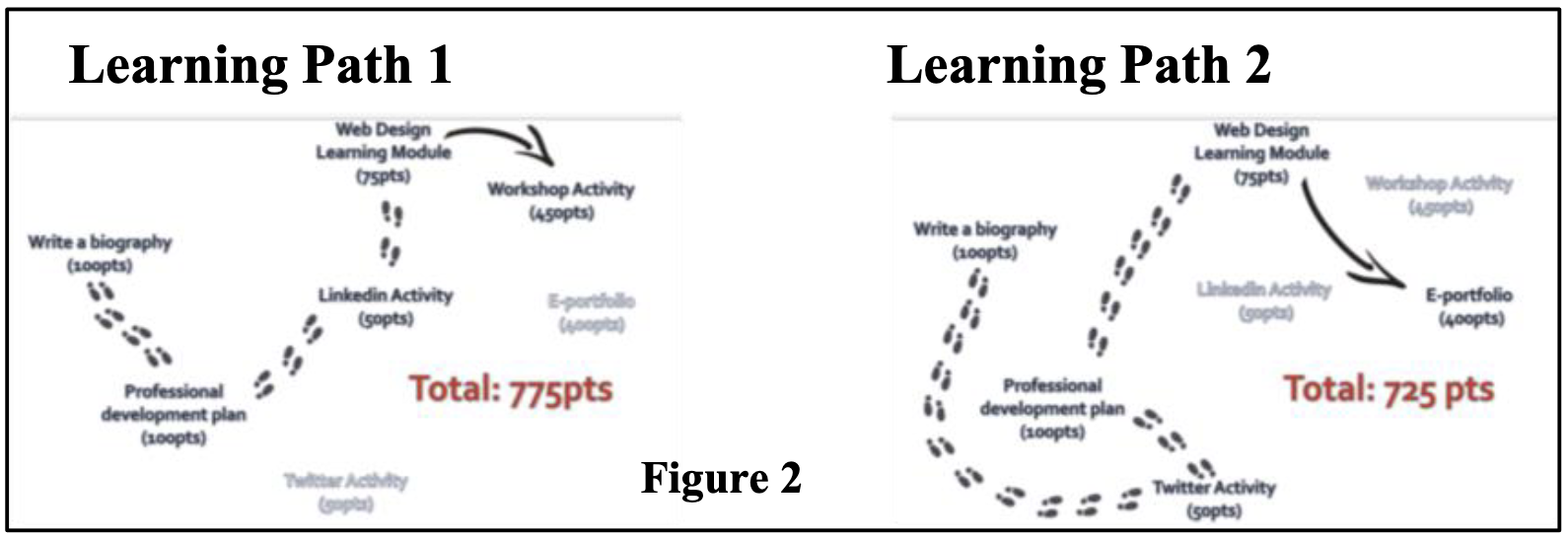

I tried to incorporate several game dynamics and mechanics to my syllabus (see figure 1). I included many ‘game choices’ for the students. In the learning game section of the syllabus, they had freedom to choose which and how many assignments to do. I also built in a ‘points, levels and badges system’ and included a ‘surprise element’ (any extra points awarded after completing the learning game would count towards a bonus percentage of the final project). I ensured the presence of difficulty cycles, not just because that is a good game design technique but it also allows for a new type of differentiation in the classroom. Several of the assignments were loosely linked, with a rationale to try and get the students to choose their own learning path by trying to establish the connections between the assignments.

For example, the student may realize that an e-portfolio is likely to include a biography and be built on a

website, therefore if the student were to complete the biography assignment and the web development

tutorial, that should make completing the big task (worth more points), in this case the e-portfolio, a lot easier (See figure 2). The idea here was to introduce some game flow to the experience, if the students feel they are learning different things at different times but still reaching the same outcome, it makes for much more interesting classroom discussions.

I also tried to incorporate some ‘action triggers’, although this area could be improved in the future. The idea was to provide some clues as to when certain assignments would be ‘unlocked’, once unlocked; a new action could be triggered.

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and judging by the course evaluations, so did the students. Some of the interesting findings were that the students seemed far more motivated and curious; they were always asking questions and for hints about ‘locked’ assignments. They covered far more workload than previous iterations of the course. I usually have one final project, and some of the students completed 3-4 final projects using this approach, based on their own choices. The syllabus, which normally disappears once received by the students on the first day of class never again to be seen, re-surfaced almost every class. The students frequently brought it over to ask about assignments, or check if they had chosen an appropriate ‘learning path’.

Nonetheless, where there are ups, there are downs. Because I was trying a new teaching strategy, I made a point to be excessively flexible with the students to give them a chance to adapt to this new format. This flexibility was my downfall. Although almost all the students were motivated to work and complete the assignments, they took some time to get used to this approach. This resulted in panic submissions towards the end of the semester (due to my flexibility with deadlines) and obviously a mammoth task of marking twelve different types of assignments simultaneously. On reflection, you cannot ask ‘Angry birds’ or a person you’re playing at ‘tic-tac-toe’ to “skip the level this time” or “just let me complete it at a different time”. Game rules are game rules and make no exceptions (unless they are planned exceptions, like rewards). This is something that I have to consider for future cycles. I will either be gamifying a larger portion of the course, or place more weight on the current gamified portion. This is because the students contributed and completed far more work than previous classes and than what I had expected. If the same levels of motivations as this semester are present, I would hate to dilute that with a weak marking ideology. I would therefore need to allocate more weight to that part of the course as some of the students did far more work than usual and felt that 30% was not sufficient for the amount of effort exerted.

Overall, this was one of the most enjoyable experiences during my teaching career. I will definitely be looking to gamify more parts of my courses and am interested in trying to use more gamification elements, especially aesthetics, as this is the only cornerstone of gamification I have yet to try and incorporate in my classes. I would highly recommend this approach to AUC faculty and would like to extend an invitation to faculty members who would like to discuss or attempt this in their courses to contact the Center for Learning and Teaching to support you with this.

References:

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Morcos, F. (2014) Game On! New Chalk Talk, 14:1. Pp.1-2 Retrieved from:

http://www.aucegypt.edu/llt/clt/ChalkTalk/Documents/Volume%2014/Vol14_Issue1.pdf